a sort of alphabet to me

words and pictures at the National Gallery in London

On a primary school trip, we walked through the red-painted galleries and sat cross-legged on the floor in front of a painting.

‘Who owns this painting?’ asked the woman who’d led us there.

We mewed a few suggestions — the Queen, or perhaps the Prime Minister — and at last the woman said: ‘You own this painting. You own a little part of every painting here.’

Then we looked at this painting that was ours. A startled woman, wrapped in silk twists toward the vivid blue of the sea and sky behind her, arm raised. She is startled mid-movement, looking at a man leaping towards her from a chariot and a group of strange characters: a boy with the legs of a goat, a naked man wearing a snake around his whole body, women with musical instruments, two plush cheetahs.

We were asked to look closer. There’s a circle of stars above the woman’s head. Over her shoulder a tiny ship in the distance. Something a little unsettling about the group of people, a leg being waved in the air while a calf’s head lies on the ground. What are the feelings here? Fear. Attention. Love? Celebration. Danger?

Finally we were given names and the story of a classical myth. Ariadne, abandoned on an island, despite helping the hero Theseus to navigate the labyrinth and defeat the Minotaur, giving him a ball of red thread so he could find his way out. Bacchus, the god of wine, falls in love with her on sight. Later she will become a constellation of stars in the sky.

The painter is Titian. He lived in Venice, the city of water, and loved the colour blue, made from ultramarine, then one of the most expensive pigments in the world.

I’ve always remembered my stir of interest from being told this odd, important painting had something to do with me, that I owned a part of it like I owned a toy or my guinea pig Stripey or the plastic princess slippers from the front of a magazine that I wore to death.

Yet it was an ownership shared with others, and I knew something about that too, and its tensions, with three siblings and lots of hand-me-down things and the elegant black-and-white cat Marie who really belonged to the twins next door but came round to our garden and through the back door and very occasionally sat on my knee.

Collective ownership is still an essential part of the ethos of the National Gallery, now marking its two hundredth anniversary with a whole year of celebration. ‘The collection belongs to the people of the United Kingdom. It is open to all’, the website states. The gallery was established by an Act of Parliament during an era of nationalism and philanthropism in the nineteenth-century. Director Dr. Gabriele Finaldi claims: ‘Public ownership and access to world-class paintings and art is just as vitally important now for a thriving civic society as it was in 1824’. Amidst this, the Gallery also stresses its global appeal, welcoming visitors both local and from overseas, part of a ‘worldwide community of museums and galleries’.

Sheila Fell (1931-1979) once said of Aspatria and Cumbria, the main subject of her paintings:

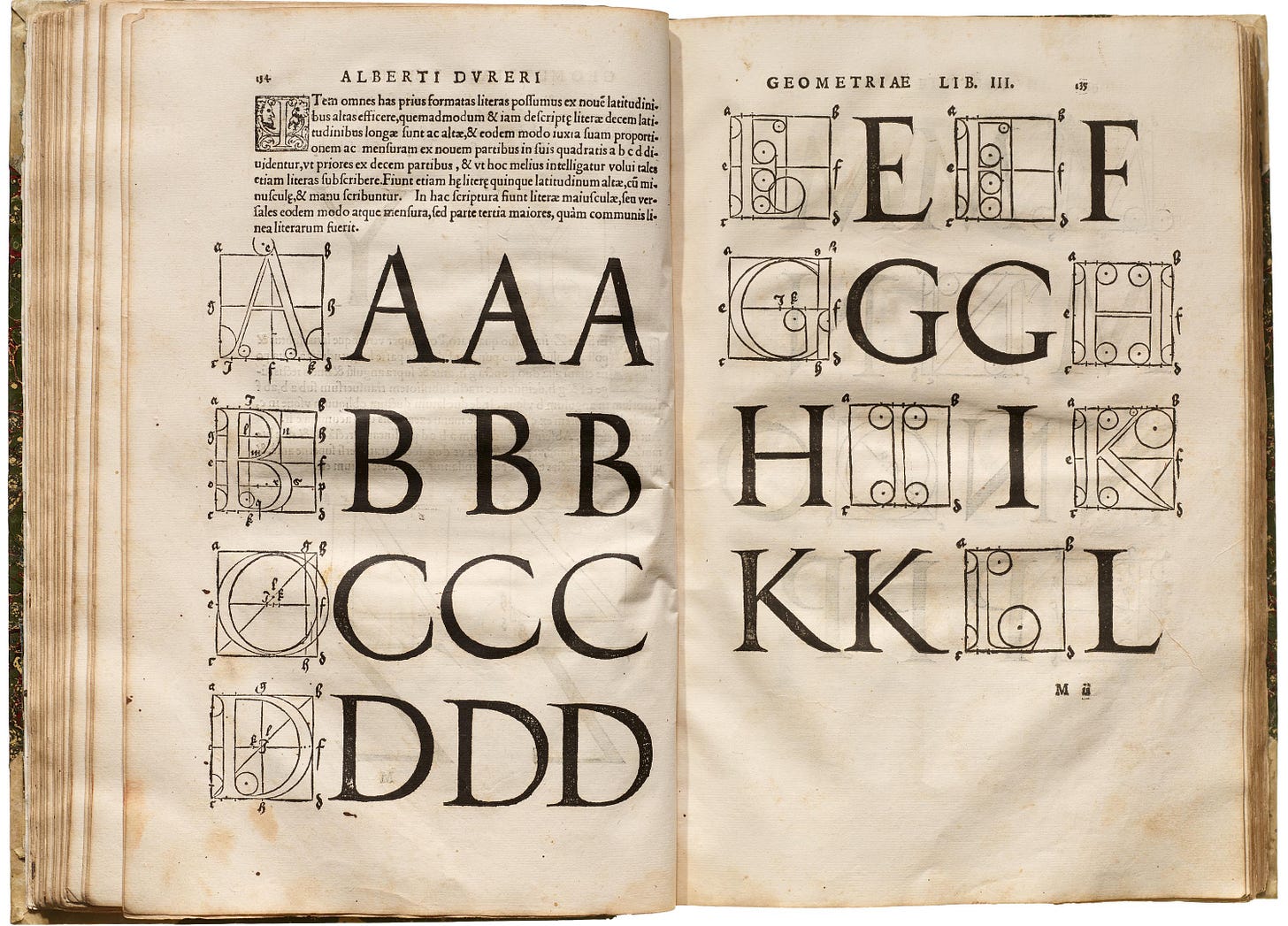

When a child’s learning to speak and read, first it learns the alphabet and then it’s able to make words and then sentences. Well, Cumberland has acted as a sort of alphabet to me, it’s a sort of A B C D, and then after that I can make words and sentences.

I’m struck by this idea of a place as an alphabet. Something learned, foundational to our ability to understand the world. A limited sequence of letters arranged and rearranged to make meaning. I think that the National Gallery in London is one of these places for me, visited again and again throughout the years, hooked into my mind because of that first visit.

We were encouraged then to look closely at paintings’ details, collecting distinguishing features: a pair of pointed wooden shoes, the gleam of a metal pin in the folds of a white headdress, angels wearing stag brooches. The distorted skull in The Ambassadors (1533), queuing behind each other to look at it from the angle that brings its proportions into focus; being taught what memento mori means. Fruit in a basket perched precariously on the edge of the table in The Supper at Emmaus (1601). Grains of sand stuck to Monet’s Beach at Trouville (1870), bringing a gust of sea air indoors.

School projects were based off the collection. My classmates and I were given sections of Beach Scene (1869-70) by Degas to recreate on cardboard, which we cut out to make a hanging three-dimensional display. My assigned figures were the two women on the far left, one a nurse huddling a baby to her chest, the other in a red headscarf. Then we wrote stories inspired by the painting, about the girl in the striped shirt having her hair combed. Adopting the perspective of objects, like the green umbrella and the windblown white bonnet. Imagining the cold clear water against the bathers’ legs and the conversation between the woman in the blue jacket and the man with a walking stick; deciding to whom the little dog belonged.

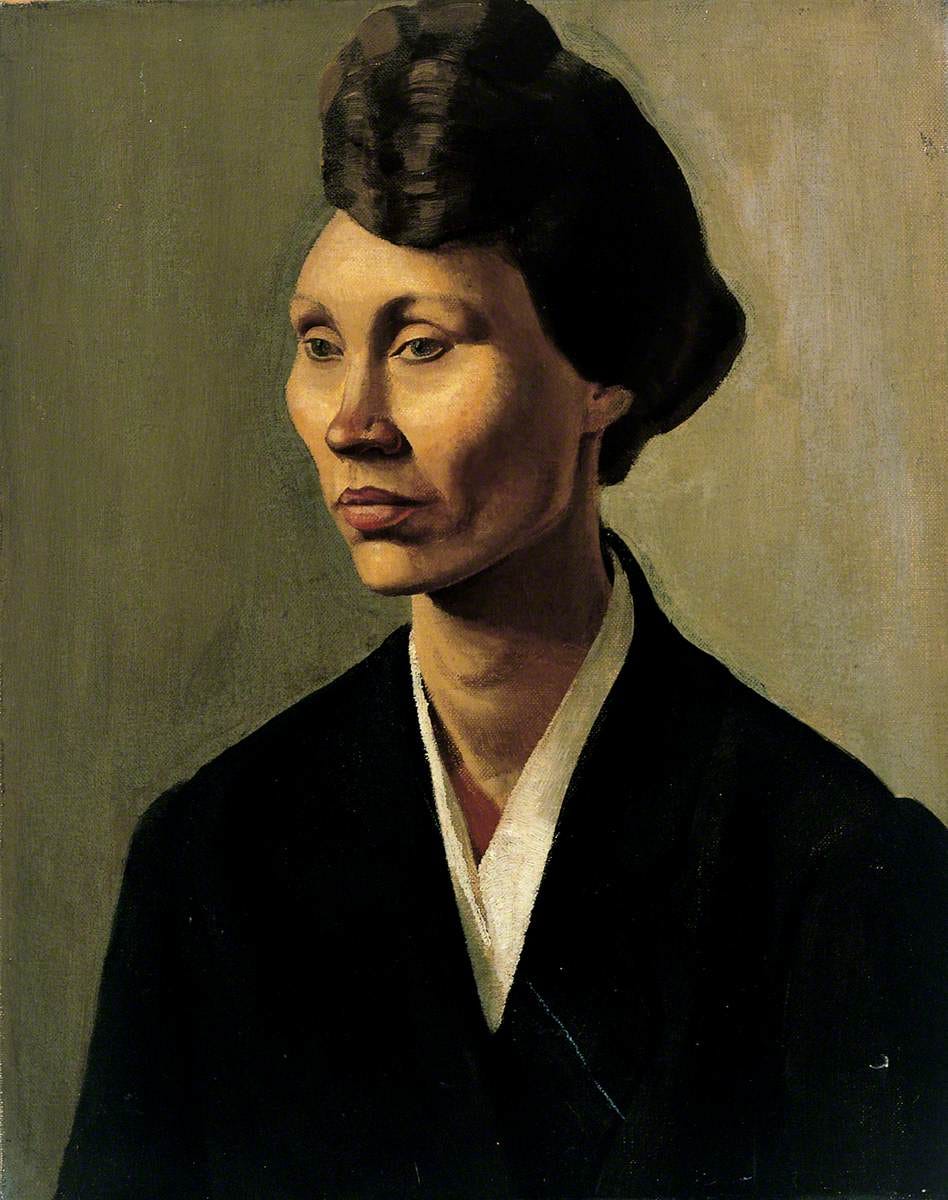

Nowadays I look at paintings by artists and they remind me of paintings from the National Gallery, as if I’ve been primed to think in quotations. Winifred Knights’ portrait of business owner Anna Fryer from 1920, for example, brings to mind the possible self-portrait of Jan van Eyck from 1433. It’s not that these paintings are particularly alike and I wouldn’t confidently claim a lineage of influence (Sacha Llewellyn suggests the the Fryer portrait may have been inspired by Modigliani). But, for me, there is something in their self-possession, the line of the bones of their faces and the hollows of their eyes, the overlapping V-shaped collars, and the intriguing arrangement of fabric and hair (or a hat?) that connects them.

At the Slade School of Art around the turn of the twentieth-century, Professor Henry Tonks encouraged his students (including Gwen and Augustus John, Stanley Spencer, and Winifred Knights) to draw daily in the National Gallery, British Museum or John Soane Museum: ‘study one picture, make a sketch of its pattern and rhythm, and buy a postcard reproduction and pin it up at home’. For a long time, artists have built up an intimacy with the Gallery’s collection, learning and adapting, creating new words from the alphabet.

Contemporary artist Molly Martin describes in her delightful newsletter how she makes numerous studies from paintings in her sketchbooks, leading workshops with art studio Eye To Pencil. She writes:

Drawing is a way of looking deeper - causing you to see more - enhancing your connection with the work and artist. There are some paintings in the National Gallery that feel like old friends because I’ve been drawn back to them so many times […]

My natural style interacts with the original transcription (which is fairly far away from the original piece) and therefore finds it’s own originality through the process of making multiple drawings.

I also started to draw the pictures around me while working as an attendant in museums and art galleries. I have a stash of crumpled pocket notebooks filled with briefing notes and sketches and scattered thoughts and plans and to-do lists.

When I make more careful drawings of works of art, attempting to retrace the artist’s hand makes me much more appreciative of the unique intensity that my version lacks. It feels freeing because it’s irrelevant whether my sketches are good or not. They are a way of close seeing, like close reading a sentence in a book. I pay greater attention to a painting’s ‘pattern and rhythm’, its negative space, the subjects’ expressions, its emotional resonance. Sketching challenges me to give a work my sustained attention.

In the 1990s, Paula Rego was commissioned by the National Gallery as their first Artist Associate to create a mural for the new Sainsbury Wing Dining Room. Last year a temporary exhibition displayed the resulting work, Crivelli’s Garden, alongside the Renaissance altarpiece that inspired it, painted by Carlo Crivelli (c.1430/5 - c.1494). Rego populates her 9-metre long painting with figures of women inspired by saints and biblical figures, reworking the subjects of the ‘Old Masters’ from the collection in her own subversive style. Several of Rego’s models were National Gallery staff, underscoring a keen sense of ‘women’s work’. Near to the right-hand corner of the mural is a woman on a stool, an open book propped on her knee, a powerful hand splayed across a white page. It’s not clear whether she sits at the beginning or the end of the painting’s narrative. But she and her book are like a lamp from which all Rego’s characters plume, genie-like.

I’ve accumulated layers of memories and associations in the rooms of the National Gallery over years that I can try to excavate like an archaeological dig-site. That’s NG I and NG VI and NG IX and so on. If I’d not been taken there while at primary school — or been indifferent to the idea of owning things at that age, or forgotten the experience of encountering Bacchus and Ariadne for the first time — art and stories may not be so important to me today. My imagination would have a different way of shaping words and pictures, in a different style of handwriting.

You can learn more about the National Gallery’s celebration plans, including loans across the UK, here.