a host of golden daffodils

the Wordsworths' daffodils, colonial legacies and the complexities of belonging

Each spring, Antiguan-American writer and gardener Jamaica Kincaid recites Wordsworth’s poem in praise of daffodils, ‘I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud’, over thousands of her own ‘jocund company’ planted in her Vermont garden. In 2007, she wrote about her changing relationship to both the poem and flower, tied to its role in the colonial education she experienced growing up in Antigua:

When I was a child, a long time ago, I was forced to memorise this poem in its entirety, written by the British poet William Wordsworth. I had to memorise many things written by British people, since the place I was born and grew up in was owned by the British, but for a reason not known to me then, of all the things I had to memorise, I took an ill feeling to this piece of literature. And why should that have been so? […] The daffodil, for one: What was a daffodil, I wanted to know, since such a thing did not grow in the tropics.

Alongside Wordsworth, Kincaid read the King James Bible, Milton, Kipling, learned all the British monarchs in succession, and sang about the white cliffs of Dover. Her childhood education is a classic example of how British cultural touchstones became tools of colonial control, far from the intentions of William and Dorothy Wordsworth in early nineteenth-century Cumberland.

This attempted enforcement of British cultural superiority to buttress imperialism is encapsulated by Thomas Babington Macaulay’s Minute on Indian Education in 1835, part of a shift in imperial policy towards ‘a civilising mission’ in the 1830s. Unlearned in languages like Sanskrit or Persian himself, Macaulay declares that none of the orientalist scholars he met could ‘deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia. The intrinsic superiority of the Western literature is indeed fully admitted […].’ Macaulay proposed that giving a section of the Indian population a western classical education would create a mediating ‘class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.’

‘I like to redeem plants from their cruelty’, Kincaid says in an interview for North State Public Radio with Jennifer Jewell in 2020. The daffodil poem, a symbol of the ‘tyrannical order of a people, the British people, in my child’s life’ came to possess other resonances when Kincaid began to live in Vermont’s climate, experiencing the ‘true spring’ the flower heralds after a cold winter. ‘One day I decided that it wasn’t Wordsworth’s fault,’ Kincaid says, ‘And so I redeemed the daffodil.’

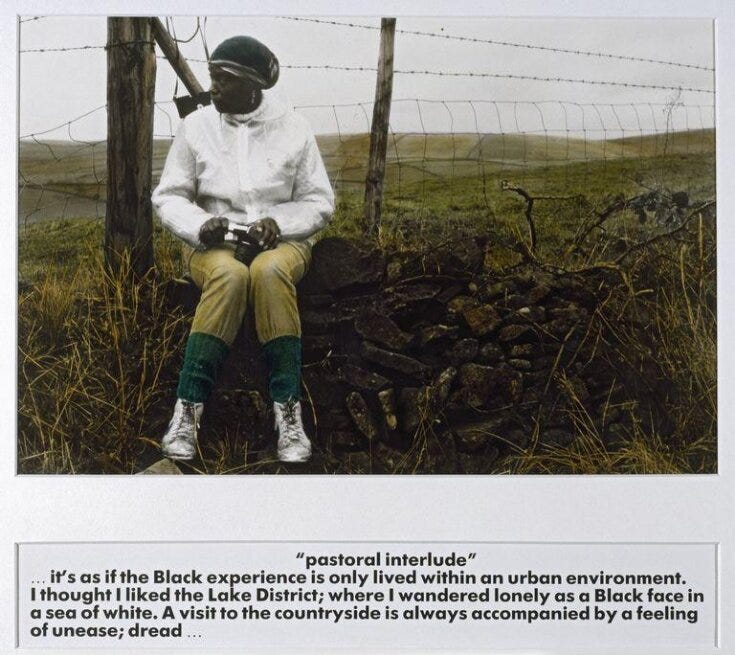

Pastoral Interlude (1982-7), one of Guyanan-born British artist Ingrid Pollard’s most famous works, also refers to the Wordsworths’ famous daffodils. The series consists of hand-tinted photographs of black people in rural environments. In one image, a woman sits on a wall and looks out of frame, her own camera in her lap, while the text underneath invokes the poem’s opening lines (‘I wandered lonely as a cloud/That floats on high o’er hills and dales’): ‘I thought I liked the Lake District; where I wandered lonely as a Black face in a sea of white.’

In ‘Landscape Interrupted’, an essay from the catalogue accompanying the 2022 exhibition Carbon Slowly Turning, Anna Arabindan Kesson writes that Pastoral Interlude seems to ‘materialise what many of us, who grew up in the former British Empire, have come to experience as diasporic subjects dealing with concepts of affiliation and belonging’, giving her a ‘language to articulate the dislocation shaped by networks of empire’. Citing the image above, she argues that the spiky wire fence separating the woman from the green fields and the woman’s averted gaze, perhaps towards something we cannot see, creates a feeling of unease: ‘What goes without saying in these images are the associations of land, nation, and belonging. The question is always, however, who belongs where?’

Thus Pastoral Interlude speaks to the ongoing exclusion of black people from the stereotypical rural idyll that Wordsworth’s ‘national property’ of the Lake District has become in popular imagination. In 2021, the Campaign to Protect Rural England reported that only one percent of visitors to UK national parks were from Black, Asian or ethnic minority backgrounds. Cumbria is considerably below the national average in terms of ethnic diversity: almost 98 percent of residents are white. Experiences of racism in the countryside and an overall lack of access to green spaces in comparison to white people perpetuates a sense that the countryside is an unwelcoming environment, although several organisations are working to change this, including Black Girls Hike and Black Scottish Adventurers.

Yet rural places across Britain have historically been more diverse than many assume. Dorothy Wordsworth often noted down her encounters with itinerant people she met on the road, or those who called at the door, in her Grasmere Journal. An entry for November, 1800, records: ‘a poor woman from Hawkshead begged — a widow of Grasmere — a merry African from Longtown.’

The Grassling (2020) by Elizabeth-Jane Burnett explores her complicated sense of belonging in the beloved region of Devon where she grew up, a place where her father’s family ‘stretches back generations’. Yet the skin colour bequeathed by her maternal Kenyan heritage causes some other inhabitants to perceive her as out of place:

While others see him as belonging, even without knowing his story, they do not see that in me. So while I am pulled towards that place by all that is deeply knotted in me, I am pulled back by those there now, who cannot see into me.

And I felt that, the last time I visited; when I wasn’t recognised, when I wasn’t noticed. When I tried to speak, but was looked over, as you do look over the things that do not matter, that bear no connection to you. Just as the bare branches of the hedge I had walked along had given nothing away as to their species, so my skin had seemed unfathomable […] If we could reveal our histories through our eyes, then perhaps she would have looked at me with more interest, more warmth — that woman in the village I had tried to talk to.

Burnett finds closeness to her ill father and belonging to her ancestors’ locality through imaginative and physical acts of ‘field swimming’, delving into the soil, becoming ‘grass made flesh’. On a walk to Haldon Forest, she imagines herself ‘tree-esque’, ‘filled with the confidence of age and stature.’ Solaced by nature, Burnett resolves to carry this with her: ‘In the times that lie ahead, as territories and common borders close, I will think of this forest. The clumps of moss, the cool water, the hills that hold. To remember this: being up, where I always dreamed of being, whenever I land against something telling me I shouldn’t be here.’

During an interview for the Guardian with Ashish Ghadiali, Pollard expressed frustration with a lack of nuance in some interpretations of Pastoral Interlude. The piece uses an article by Robert Macfarlane on ‘eeriness’ in the English countryside as an example. It takes Pollard’s texts as straightforward captions to her photographs, autobiographical expressions of her personal alienation. Yet she intended the texts to exist in tension with the images (revealing our reliance on words to anchor the meanings of photographs). ‘They’re holiday snaps.’ Pollard says, ‘People are having fun in those photographs.’:

People immediately say [about Pastoral Interlude]: ‘It’s about alienation. It’s about white landscape, Black people. It’s eerie,’” Pollard continues. “It gets bashed into whatever shape people want to put it in.” By contrast, she sees that piece and her own work more broadly as reflecting a lifelong engagement with the British landscape in all its complexity. Referring to an image from the series where the model sits, camera in hand, on a dry stone wall, Pollard tells me to turn my attention towards the fencing, the hedgerows and the hilltops behind her: “Look at that landscape,” she says. “It’s a managed landscape, the trees have been taken away, there are dry stone walls, there are sheep. Everything about it is fabricated for industrial rural use. The barbed wire, the telegraph pole, the tarmac. Stereotypes about Black people are constructed in exactly the same way.’

This awareness of the essentially constructed nature of the British countryside is consolidated by Pastoral Interlude’s evocation of the history of landscape painting. Gainsborough’s comical depiction of Mr. and Mrs. Andrews (c. 1750) before their Essex acres, often vaunted as one of the UK’s most iconic artworks, was painted at a time of accelerating enclosure, transforming communally cultivated open fields into large farms to suit landowners. In Ways of Seeing (1972), John Berger observes the class-based proprietary air of Gainsborough’s couple:

Theirs is private land. Look at their attitude towards it. The attitude is visible. If a man stole a potato at that time, he risked a public whipping. The sentence for poaching was deportation. Without a doubt, one of the principal pleasures this painting gave to Mr. and Mrs. Andrews was the pleasure of seeing themselves as the owners of their own land.

The seated position of the woman on the wall in Pastoral Interlude is perhaps a conscious echo of Mrs Andrew’s posture in front of a tree by the cornfield, a view of grazing sheep and more fields (another highly ‘managed landscape’) beyond her. Both women’s hands are near their knees. Pollard’s sitter holds a camera, however, a means of capturing her own images, while there is an unfinished white space on Mrs. Andrews’ skirt that may have been reserved for a baby, the expected son and heir to these possessions. The pointed heels encasing Mrs. Andrews’ barbie feet contrast with Pollard’s subject’s thick walking socks and sturdy shoes, practical attire for walking amongst the land instead of merely surveying it.

Pollard writes of her art in her PhD thesis:

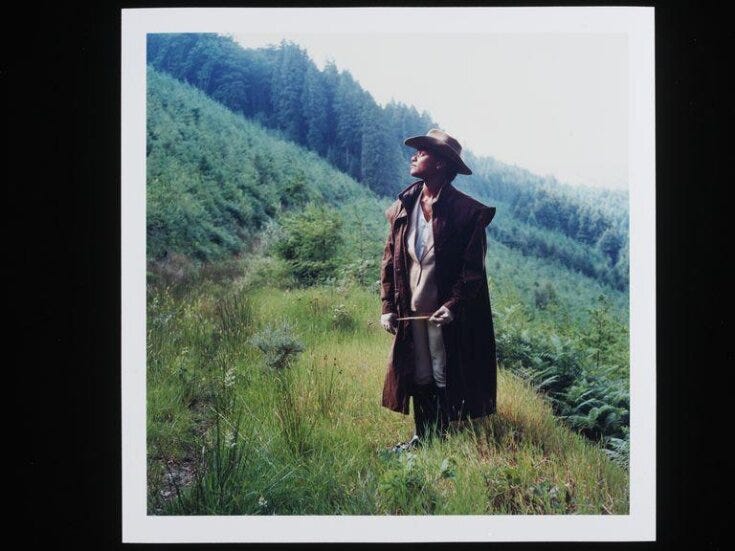

I favour the figures within my landscapes image as centrally placed, rather than occupying liminal spaces in the frame and or subservient roles. This is a deliberate tactic to dominate the composition, to counter historic paintings which were commissioned by privileged land owners and represented control of the natural elements.

For example, Wordsworth’s Heritage (1992) ‘claims a national belonging through reimaging the Lake District; placing of correctly attired black hikers claiming their place amongst the hills of a centrally identified, Wordsworthian, Lakeland postcard.’ While engaging with colonial legacies, these reclamations assert the right to enjoyment and belonging in the British countryside, aligning with the spirit of Kincaid’s redemption of the daffodils.

In a chapter of Grassling titled ‘Daffodils’, Burnett travels to visit her father on his eightieth birthday. She gathers instances of the colour yellow as a gift, inspired by ‘the daffodils in the copse I picked when I last saw him’. Her list includes primroses and broom alongside hi-vis jackets and Morrisons. Like Kincaid, Burnett brings up the daffodils’ hopeful association with the end of a cold season: ‘the daffodil is the first time we dare to believe in summer, as the days fill with its quiet suns.’ She writes:

It’s easy, seeing a field of daffodils, to believe in colour therapy. To sense the power of the strident singing yellow and even to see how each of the spectrum colours might resonate their own energies. I bring him flowers. And if the colour is light, of differing wavelengths, I wonder, do I bring him light? […] As I cover the distance between us, I ask: how do you travel to another person? Physical presence gets you somewhere, but once together, verbal language can fall so short. […] The soil begins to show me new ways to reach him. We will short-circuit speech through colour, gathering our yellows while we may […]

In some ways, Burnett’s father seems to embody the quintessential British nature lover who traditionally dominates the genre of nature writing: English, author of a local history book, white, male. Expressing the great love between father and daughter yet expanding nature writing in innovative ways, Grassling might partly be interpreted as a claim of inheritance. Burnett can both subvert and belong to this kind of rural Englishness. Despite those who view her as ‘other’, she self-grounds in her landscape:

All the skin of me, the pigment, the falling dust, is called to the soil. All the water of me, the churning motion, is called to the fish: the bony lobe-fins, ancestors of dinosaurs and mammals, whose fossils remain in the Devon rocks. All the heart of me, the pulsing inside, is called to the pulsing outside: the grass, the birds, the insects, the worms; and further, to the beating that continues beyond the earth, beyond anything tangible: to my father’s fathers.

If you’d like to read more:

As well as Wordsworth’s poetry becoming a staple of British colonial education, the Wordsworths were also materially connected to Britain’s growing empire. Their father was a law-agent for the Lowther family, who were involved in the slave trade. Their brother John Wordsworth was a captain of the East India Company. When he died tragically at sea in 1805, Coleridge noted down that his death was ‘a loss to the concern’, the household to which John was to retire with his financial contributions (Source: Polly Atkin’s Recovering Dorothy). The National Trust’s Colonial Countryside project researched many of Britain’s country house links to the slave trade, naming 93 properties so far. Academic and co-editor of their report Corinne Fowler talked to Inkcap Journal in 2021 about their work:

Efforts to inject the myth of merry England with a dose of historical reality are frequently met with hostility, explains Fowler: “I think there's a common assumption that the countryside has historically been a place where only white people lived, and certainly where white people more naturally belonged, than people of colour,” she says. Her work shows decisively that this was never the case.

Jessica J. Lee, editor of the Willowherb Review, has also written about the impact of British literature in her essay ‘How the Literature of Empire Shaped my View of the Natural World’, in particular relation to the heather of Brontë country:

I did not need to understand the workings of empire for it to shape me profoundly. Simply through repetition, through their representation in the storybooks and novels deemed classics of literature, these British landscapes came to signify for me wildness, romance, an ideal in nature. I paid no attention to flora outside my window, beyond the suburbs where I grew up—in a flat land of canola and corn, where forests were built of sugar maples and pines.

In ‘Disturbances of the Garden’, Jamaica Kincaid writes about her relationship to gardening and the garden’s links to imperialism, possession and the story of Genesis and the Garden of Eden:

My mother was a gardener, and in her garden it was as if Vertumnus and Pomona had become one: she would find something growing in the wilds of her native island (Dominica) or the island on which she lived and gave birth to me (Antigua), and if it pleased her, or if it was in fruit and the taste of the fruit delighted her, she took a cutting of it (really she just broke off a shoot with her bare hands) or the seed (separating it from its pulpy substance and collecting it in her beautiful pink mouth) and brought it into her own garden and tended to it in a careless, everyday way, as if it were in the wild forest, or in the garden of a regal palace. The woods: The garden. For her, the wild and the cultivated were equal and yet separate, together and apart.

I hoped to get this issue out before the daffodils in Edinburgh passed but things got a bit too hectic. The bluebells and the hawthorn are out now, even a few elderflowers, so spring is quickly passing into summer where I am. I hope you enjoyed reading anyway! I’ve had some pieces of writing published on other platforms, one exhibition review of TIDAL at Cooke’s Studios, Barrow-in-Furness, a book review of Nona Fernández’s Voyager and an essay looking at the affinities between Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi and C.S. Lewis’ The Magician’s Nephew. Check them out if you’re interested.